Learn about Canine Parvovirus (CPV)

ETIOLOGY

Canine Parvovirus (CPV) infection emerged in the late 1970s as a worldwide disease with high morbidity and mortality. CPVs are small, non-enveloped DNA viruses that require rapidly dividing cells for their replication (Figure 1). All Parvoviruses, CPV2, and 1 are highly stable and resistant to adverse environmental influences. With the gradual development of immunity in the adult dog population, a result of natural exposure and vaccination, the clinical model of the disease has changed. The most common clinical presentation now is acute enteric disease in young dogs between weaning and six months of age. Canine Parvovirus is now considered a mutant of the Feline Panleukopenia Virus (FPV).

Parvovirus structure. (Art of Kip Carter © 2004 University of Georgia Research Foundation.)

EPIDEMIOLOGIA

CPV is highly contagious, and most canine species are susceptible to infection, with transmission predominantly occurring through the oral-fecal route. Infected dogs shed a large number of viruses in their feces (109/g from the 5th or 6th day of infection). The low virus dose required for establishing the infection and the ease of mechanical transfer are important additional factors contributing to the spread of the infection.

When the disease occurs, the clinical presentation is more severe in young growing canine puppies harboring intestinal helminths, protozoa, and certain enteric bacteria such as Clostridium perfringens, Campylobacter spp., and Salmonella spp.

The incubation time for the original CPV2 strains was 7 to 14 days. For CPV2a, 2b, and 2c strains, the incubation period can be 4 to 6 days.

PATHOGENESIS

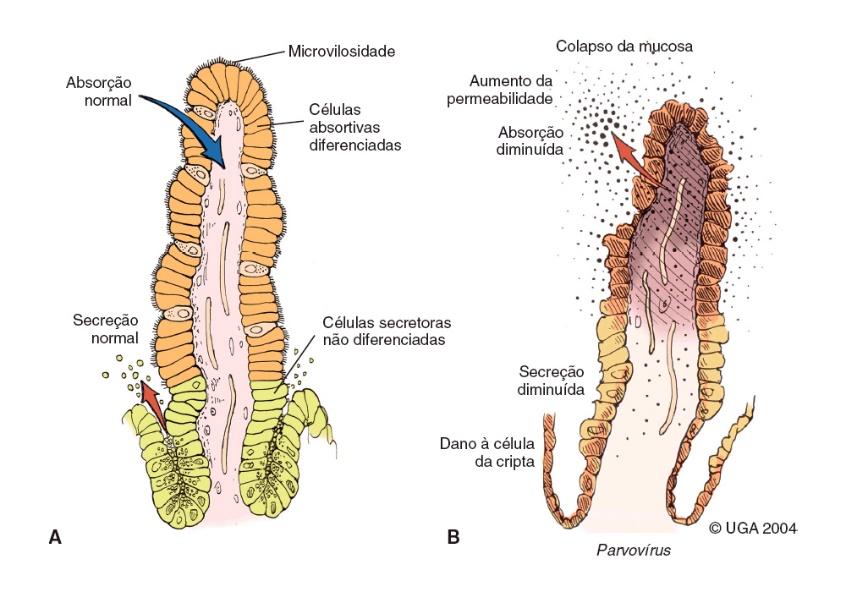

The virus initially replicates in the lymphoid tissues of the oropharynx, mesenteric lymph nodes, and thymus, spreading to the intestinal crypts of the small intestine through viremia, which occurs 1 to 5 days after infection acquisition. After viremia, CPV localizes, in most cases, in the gastrointestinal lining epithelium and buccal and esophageal mucosa, as well as in the small intestine, lymphoid tissue, and bone marrow.

Parvovirus infects the germinal epithelium of the intestinal crypts, causing destruction and collapse of the epithelium. The loss of intestinal crypt cells leads to flattening of the villi, resulting in reduced absorptive and digestive capacity, leading to diarrhea. There may be extensive hemorrhage into the intestinal lumen in severely affected puppies. The destruction of intestinal mucosal lymphoid tissues and mesenteric lymph nodes contributes to immunosuppression, allowing the proliferation of Gram-negative bacteria with secondary invasion of the injured intestinal tissues. This can lead to endotoxemia, resulting in endotoxic shock.

The active shedding of CPV2 strains begins on the third or fourth day after exposure, generally before the onset of frank clinical signs. CPV2 is extensively eliminated in the feces for several weeks after infection. Serum antibody titers can be detected as early as 3 to 4 days after infection and remain reasonably constant for at least 1 year.

CLINICAL SIGNS

CPV infection has been associated with three main tissues – gastrointestinal tract, bone marrow, and myocardium – but the skin and nervous tissue can also be affected, where the animal’s immune status highly determines the form and severity of the disease. Most dogs have inapparent or subclinical infections, especially in canine puppies with intermediate levels of maternally-derived antibodies, which can protect them from the disease but not from infection. Diarrhea, often bloody, develops within 48 hours, and in severe cases, there may be severe hemorrhage. The feces have a foul odor. Intestinal parasitism and concurrent viral or bacterial infections can exacerbate the disease. Affected dogs deteriorate rapidly due to dehydration and weight loss. Animals that survive the disease develop lasting immunity.

ENTERITE

Enteritis caused by CPV can progress rapidly, especially with infection by newer strains (a, b, c) of CPV2. Vomiting is severe, followed by diarrhea, anorexia, and rapid onset of dehydration. The feces are yellow-gray and may contain blood streaks or become dark. There may be elevated rectal temperature (40 to 41°C) and leukopenia (especially lymphopenia), particularly in severe cases. Animals that develop the systemic inflammatory response syndrome are more prone to mortality. Death can occur 2 days after the onset of the disease and is generally associated with gram-negative sepsis or disseminated intravascular coagulation, or both.

NEUROLOGICAL DISEASE

CPV can potentially cause primary neurological disease, but it is more common as a result of hemorrhage in the central nervous system (CNS) due to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), sepsis, or acid-base balance disorders. Concurrent infection with other viruses, such as Distemper virus, is also possible.

MYOCARDITIS

Myocarditis can occur due to in utero infection or in canine puppies under 6 weeks of age. Generally, all puppies in a litter are affected. Those with CPV2-induced myocarditis typically die or succumb after a short episode of dyspnea and vomiting. Signs of cardiac dysfunction may be preceded by the enteric form of the disease or may occur suddenly without apparent prior affection.

DIAGNOSIS

The sudden onset of bloody and foul-smelling diarrhea in a young dog (under 2 years of age) is generally considered indicative of CPV infection. Leukopenia, although not found in all dogs, is usually proportional to the severity and stage of the disease at the time of blood collection. Canine puppies that die from the disease generally have total leukocyte counts equal to or less than 1,030 cells/μ ℓ and have persistent lymphopenia, monocytopenia, and eosinopenia in the first 3 days of hospitalization. Samples for laboratory examination should include feces, blood, and other tissues. The definitive early diagnosis in affected animals is supported by demonstrating the virus or viral antigens in the feces.

DETECTION IN THE ORGANISM

Fecal antigen tests are specific for detecting CPV infection. Keep in mind that the fecal shedding period is usually short, corresponding to the first days of clinical illness. With an incubation period ranging from 4 to 6 days, it is rare to detect CPV strains for more than 10 to 12 days after natural infection, and shedding can be intermittent. Therefore, negative results during or after this period do not rule out the possibility of CPV infection.

Positive results confirm infection, or they may be found when using vaccines with live attenuated CPV. In contrast to strongly positive results typically seen after natural infection, the vaccine virus can lead to a weak false positive result in dogs 4 to 8 days after vaccination. Quantitative testing for the virus has been able to distinguish vaccination-induced infection from natural infection because, in the latter case, the viral load is higher.

ANTIBODY DETECTION

Serological tests can be useful for evaluating maternal antibody titers in unvaccinated canine puppies. A high antibody titer obtained from a single serum sample collected after an unvaccinated dog has been clinically ill for 3 days or more is diagnostic for CPV infection. It is also possible to demonstrate rising antibody titers (seroconversion) when comparing samples from the acute and convalescent phases within 10 to 14 days. Commercial immunochromatography kits (Accuvet CDV/CPV Ac Test) are available for in-office use, providing semi-quantitative estimates of IgG titers.