Learn about Canine Influenza and its diagnosis

ETIOLOGY AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

In 1999, a strain of equine influenza virus – H3N8, circulating in horses, underwent adaptive evolution through induced genetic mutations and subsequently infected dogs. The virus was first isolated from dogs during a respiratory disease outbreak in Florida in 2004 and has since been found in isolated cases in other states. It was determined that the H3N8 virus from the Florida outbreak was a Canine Influenza Virus (CIV) adapted to the host, replicating readily in dogs. This new canine strain has the entire genome of the equine virus, with minimal identified modifications. However, this modified H3N8 virus, which replicates and spreads easily among dogs, does not establish a productive infection in horses, felines, or birds.

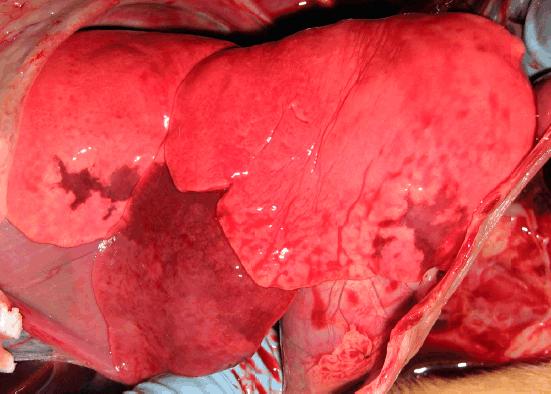

Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 1. Canine influenza virus-induced lung lesions in a young dog 3 days after exposure. Pulmonary congestion, consolidation, and petechial hemorrhages are visible. (Merck Animal Health.)

PATHOGENESIS

Intratracheal and intranasal inoculation in dogs produced fever (above 39°C) for 2 days, with no signs of respiratory disease. 14 to 15-week-old puppies negative for antibodies and infected via intranasal route developed respiratory signs and lung lesions (Figure 1), with viral replication and seroconversion demonstrated. Similar lesions can also be found in adult dogs infected through intranasal and intratracheal administration of the virus. Although respiratory tract inflammation and lymph node involvement are prominent, pulmonary consolidation to the extent of consolidation is uncommon in experimentally infected dogs. Viral replication and shedding were highest during the initial incubation period, lasting 2 to 5 days, and decreased rapidly thereafter; a lower level of shedding persisted for up to 7 to 10 days. Dogs with subclinical infection still shed the virus, albeit at lower levels than those observed in more severely affected dogs.

CLINICAL SIGNS

After the introduction of the virus into institutions with susceptible dogs, the severity and prevalence of the infection may suddenly become more noticeable than with other causes of canine infectious respiratory disease. The longer dogs that have never been infected remain in an endemic shelter, the higher the likelihood of infection. Clinical signs in dogs affected during the first identified outbreaks ranged from fever, tachypnea, and mucopurulent nasal discharge to self-limiting cough (lasting 10 to 14 days). More severe and persistent respiratory manifestations are associated with the development of pneumonia, which can be confirmed through chest radiographs.

Most dogs recover, with a minority dying from hyperacute disease, and at necropsy, death is associated with pulmonary, mediastinal, and pleural hemorrhage. Histological changes included tracheitis, bronchitis, and suppurative bronchopneumonia. Following these outbreaks, dogs with no history of respiratory disease may have high antibody titers against these viruses, indicating rapid spread of the infection with subclinical disease in many dogs and to many other kennels, shelter institutions, and individual pets.

DIAGNOSIS

The signs of CIV infection are similar to those caused by other agents of canine infectious respiratory disease. Specific tests should be done to confirm the disease, which is sometimes important in large-scale outbreaks when confirming the causes is necessary to aid in control measures, starting from the detection of the virus, isolated from nasal swabs (preferred) or ocular swabs or during the first 4 days of infection. The clinical signs of this infection are similar to those caused by Group C Streptococci (Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus), which can cause outbreaks of acute respiratory disease, often fatal, in many host species, including dogs.

References

Infectious Diseases in Dogs and Cats / Craig E. Greene; translated by Idilia Vanzellotti, Patricia Lydie Voeux. 4th ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan, 2015.